Future of Floods | Overview

Control system

Surface water management will improve with sustainable drainage systems becoming mandatory for new developments, but what regulatory structure is needed to make it work? Tom Johnson investigates.

The frequency and severity of extreme flooding in the UK have increased in recent years as a result of climate change, but until recently there has been a gap in legislation to drive change to tackle to issue.

In January, the Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (Defra) Review for implementation of Schedule 3 to The Flood & Water Management Act 2010 set out the scale of the problem. Schedule 3 was shelved when sustainable drainage systems (SuDs) approval in England became part of National Planning Policy Framework approval in April 2015. However, this was not a success in terms of use of SuDS.

Defra’s new document states that there is a 1% chance every year that monthly winter rainfall in the UK will be 20% to 30% higher than previously recorded.

These high rainfall events combined with centuries of building hard infrastructure and houses with little or no drainage for rainwater, other than the sewer system, has put a high number of properties at risk from surface water flooding. The National Infrastructure Commission (NIC) has estimated that around 325,000 properties are in areas at the highest risk – meaning there is a more than 60% chance they will flood in the next 30 years. Without action the NIC estimates that another 295,000 properties could be put at risk.

A solution to this problem, which the industry has been demanding for years, is the adoption of Schedule 3 of the Flood and Water Management Act 2010.

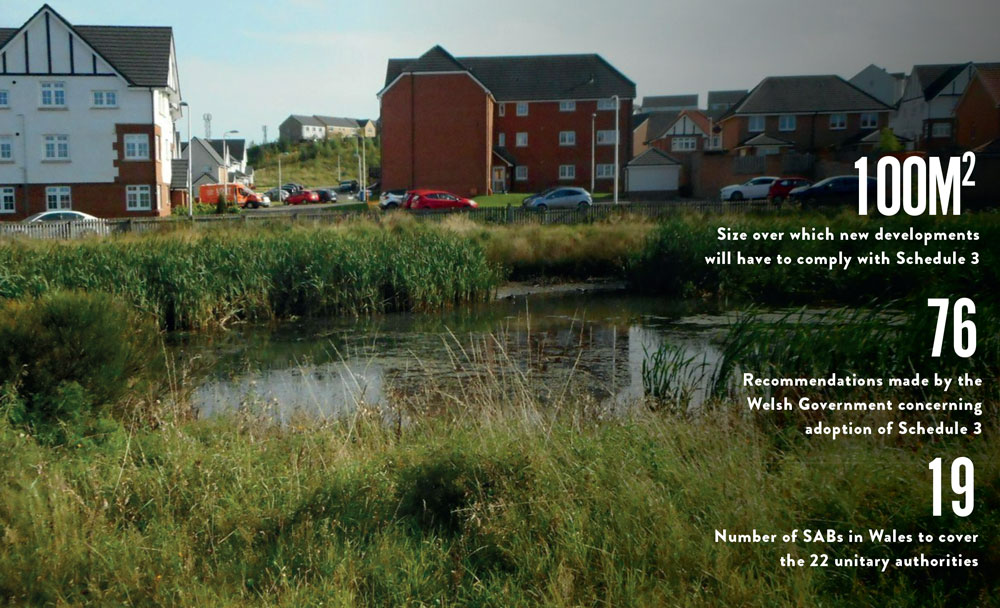

This requires new developments of more than 100m2 to include SuDS that have been authorised by sustainable drainage approval bodies (SABs) at the planning application stage.

SABs are a service delivered by the local authority to ensure that drainage proposals are fit for purpose and designed and built in accordance with national standards.

SuDS are essentially attenuation features that provide storage for surface water run off following heavy rainfall or slow the flow of such water into the existing drainage system.

SuDS examples include soakaways, grassed areas and wetlands.

Schedule 3 will be implemented in England next year, after being adopted in Wales in 2019. Currently new developments in England have an automatic right to connect surface water drainage to nearby sewerage infrastructure. This has increased the burden on ageing Victorian sewerage systems. Implementing Schedule 3 makes this right conditional on the drainage system being approved before construction work can start.

Using SuDS will reduce the impact of a new development on existing drainage systems and surrounding roads by containing additional surface water run off created by the development.

KEY FACT

325,000Number of properties in areas of highest flood risk

“When you build a new development and you allow the water to drain correctly, you control the flooding and you control the water quality.

“It then becomes very obvious to you that, prior to this point, we’ve created a huge environmental and flood problem across the country,” says Welsh Government sustainable drainage senior advisor Ian Titherington.

SuDS as a solution to the rising flood risk is not a new idea. Sir Michael Pitt’s review of the summer 2007 floods recommended them as an effective way of reducing surface water flooding risk and of reducing the burden on sewerage systems.

As WSP SuDS technical director Chris Patmore points out, the industry has been waiting a while for the adoption of Schedule 3 to be brought forward. “Everybody realised that this kind of approach was necessary back then. It’s just taken a long time to come to fruition,” he says.

While the implementation of Schedule 3 is widely lauded as necessary, developers face a number of challenges associated with it.

Polypipe green urbanisation innovation manager Charlotte Markey says developers and designers will have to start thinking in a different, “more creative way” about drainage.

“It doesn’t just become a basic civil engineering approach. It becomes something whereby you have to have green, blue and conventional grey infrastructure assets working together in tandem,” she says.

Green infrastructure assets include open green spaces such as parks and gardens, as well as urban greening features such as street trees. Blue infrastructure relates to canals, rivers and floodplains and grey infrastructure is traditionally engineered water management systems such as wastewater treatment plants and pipelines.

INFRASTRUCTURE EXEMPTION

Many infrastructure projects are exempt from Schedule 3. In Wales schemes that includes the laying of railway track bed or the construction of trunk roads do not have to be approved by a SAB. In England, Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects will be exempt.

Defra plans to seek feedback from Network Rail and National Highways about how they believe the further scope of exemptions for infrastructure projects should work.

Titherington does not believe that all railway and highways projects should be considered as exempt.

“That’s a bit of an urban myth really,” he says.

“Anything associated with new rail is not excluded. If you have a platform, if you have a car park, if you have a railway station, that will need to be authorised by a SAB.”

“We’ve created a huge environmental and flood problem across the country

Patmore has also noticed there is a crossover with highways projects.

“There will be a lot of urban regeneration highway alteration schemes which will be dragged into the Schedule 3 process,” he says.

He anticipates that after the implementation of Schedule 3 a lot more SuDS will be installed in traffic calming schemes and other small scale highway projects.

The infrastructure exemptions are “significantly flawed”, according to consultant PJA’s associate and national water resources lead Alison Caldwell. This is due to highways being the biggest culprit when it comes to waterways pollution and flooding caused by surface water runoff.

Further to this, Caldwell believes that the 100m2 rule should be a blanket regulation which applies to any development over that size.

“If you are doing very minor works on 100m2 of highway, then I don’t think they should have to rip it all outand put in this pristine, incredible system,” she says. “But If they’re putting in a new link road then I absolutely think they should have to.”

IMPLEMENTATION

As a result of implementing Schedule 3, developers must show that their drainage systems comply in their planning applications, with the installation monitored and handed over from the developer to the SAB, post-construction.

PJA water resources team associate Andy Johnson is pleased the drainage aspect of an application is being brought to the fore. He is glad that sustainability and drainage will be considered in the initial masterplanning of a development. This is because their design and cost are front-loaded at the beginning of the project and not added as an afterthought.

A consultation about how Schedule 3 will be implemented in England is expected, but the expectation is that it will follow Wales’ model of having SABs preside over planning applications and make final decisions about whether to accept a planning application based on its drainage design.

Rain gardens with attractive planting have helped SuDS gain favour with the public

Rain gardens with attractive planting have helped SuDS gain favour with the public

Titherington says: “I think having a SAB team close to the planning authorities is the only way to make it work.”

There are currently 19 SABs in Wales covering its 22 unitary local authorities. Some have joined together to deliver the SAB function through a regional approach.

Once the drainage system is built, the Welsh SAB model also has the SAB taking ownership and maintaining it. This is something Caldwell agrees with.

“I’m quite supportive of the fact that it [the SAB] will be the lead authority or taking ownership, rather than a water company or another individual,” she says.

“They [SABs] have the responsibility and will continue to hold the statutory of responsibilities when these things go wrong or when flooding occurs.”

This works, according to Caldwell, because SABs will be intrinsically linked to flood risk management authorities and will have a working relationship with organisations like the Canal & River Trust, the Environment Agency and other key players.

“It feels a bit counter-intuitive to set something up entirely separately to a council when actually that’s what a council does. That’s the council’s remit,” Caldwell continues.

THE WALES EXPERIENCE

In July, the Welsh Government released a report with 76 recommendations for how England could make improvements to the Schedule 3 process.

A key recommendation concerns project delays, so if a planning application is accepted before the implementation of Schedule 3, but construction does not start by a certain date, the developer will have to re-seek SAB approval. This addresses an issue where developers in Wales submitted a large number of planning applications before the date when Schedule 3 was implemented to avoid complying with the legislation, yet did not start construction until much later.

“Councils in England are going to find it incredibly difficult to create a SAB team for every district councilAnother cause for concern in Wales is a major skills shortage and lack of resources SABs have faced in attempting to recruit officers with the technical knowledge and drainage background to enforce the regulation.

“This is my personal opinion, but councils in England are going to find it incredibly difficult to create a SAB team for every district council. In Wales it’s been challenging but there are single unitary authorities with potentially more resources than in England,” Titherington says.

This boils down to a lack of funding to recruit suitably skilled civil engineers with technical knowledge, according to Titherington.

While everyone agrees that implementing Schedule 3 is the right thing to do, Patmore says that it will be some time before the effects are felt. Added to this, Schedule 3 only applies to new developments and Patmore points out that it will only be when all developments are tasked with retrofitting SuDS that flood risk is really challenged.