Future of Flooding | Lower Otter Restoration Project

Back to nature

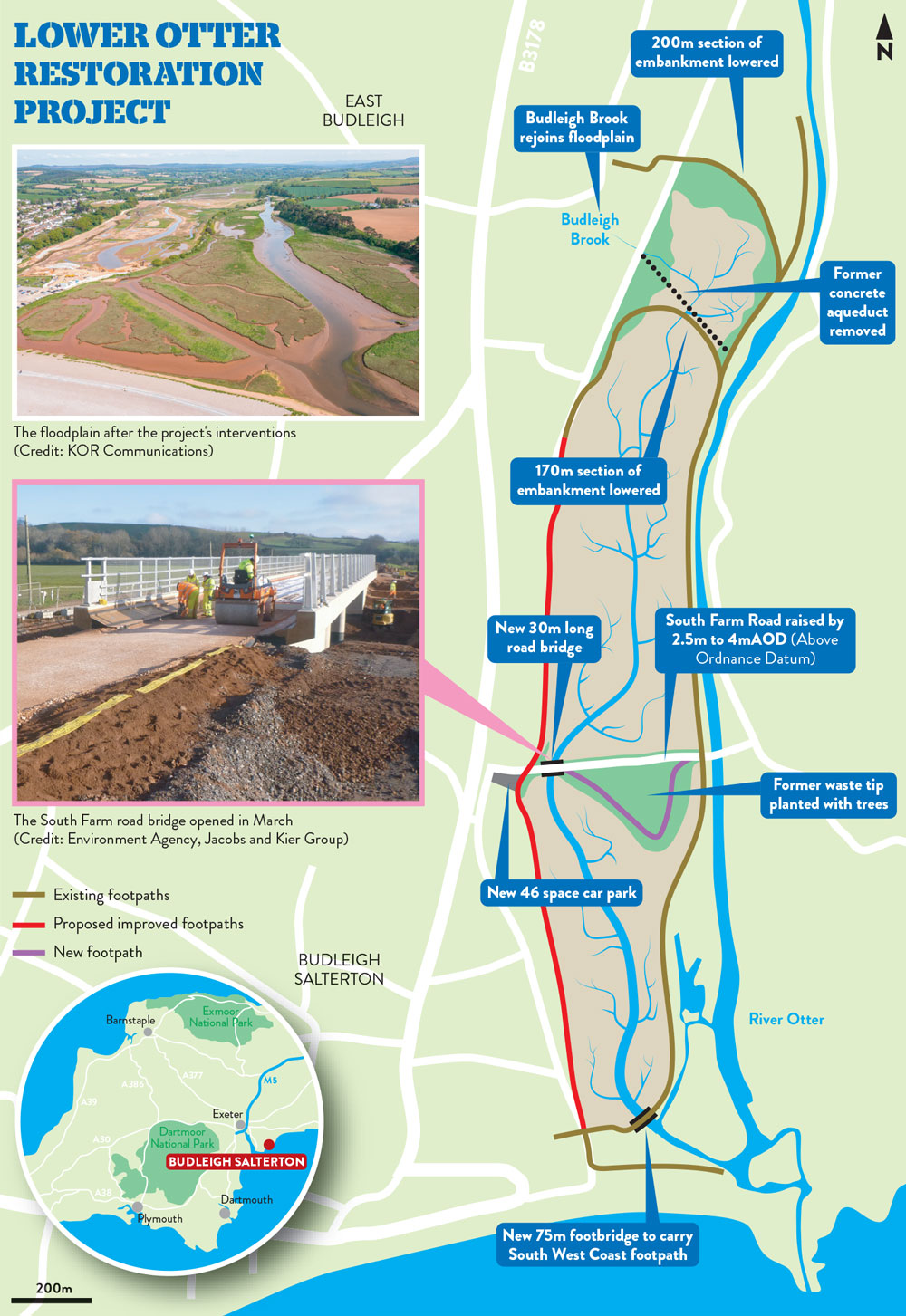

Flood mitigation work currently underway in Devon is a showcase for how engineers can sympathetically reconnect an artificially managed floodplain to a river estuary. Rob Hakimian reports.

Transforming 55ha of farmland land into an intertidal habitat while protecting 2,100 properties from flooding in one project is an impressive outcome. But this is what the £27M Lower Otter Restoration Project (Lorp) in Devon has achieved. The project has taken years of planning, engagement, obtaining consents and engineering in difficult conditions.

The land in question is owned by Clinton Devon Estates and lies where the River Otter meets the sea on the Devon coast. It is criss-crossed by embankments built by farmers 200 years ago to create agricultural land. These barriers cut off the Otter estuary from most of its floodplain.

The land in question is owned by Clinton Devon Estates and lies where the River Otter meets the sea on the Devon coast. It is criss-crossed by embankments built by farmers 200 years ago to create agricultural land. These barriers cut off the Otter estuary from most of its floodplain.

With the recent rises in sea level and more frequent heavy rainfall events, excess water would build up in the remaining floodplain and eventually overtop the old embankments. This excess water would then be held back by the embankments, unable to rejoin the estuary, prolonging local flooding and making a cricket club, footpaths and a road unusable.

Such events were becoming more frequent as well.

The Environment Agency decided to use a combination of hard and soft engineering to reconnect the estuary to the entirety of its historical floodplain. The aim was to increase flood resilience and restore the mudflats and salt marshes.

The project is part of an Anglo-French cross-border intertidal habitat reclamation initiative.

The Environment Agency and the Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (Defra), worked with East Devon Pebblebed Heaths Conservation Trust, French natural habitats protection body Conservatoire du Littoral and the local authorities for Quiberville and Terroir de Caux in Normandy to create the Promoting Adaptation to Changing Coasts (Pacco) crossborder initiative.

Pacco is using Lorp and a project in a commune known as Val de Saâne as demonstrators.

The Environment Agency committed over £19M to Lorp and submitted the Pacco project to the European Union’s Interreg VA fund, which promotes research and innovation, environmental protection, sustainable transport and health and social care. This raised another £6.6M for the project. Further funding came from South West Water.

SENSITIVITY

Reconnecting the river to its floodplain involved breaching the embankments, while creating a more natural habitat meant sympathetically removing swathes of vegetation.

Meanwhile, enabling humans to continue moving around the area required the construction of new flood-resilient infrastructure.

Through it all, being environmentally sensitive was of utmost importance. “It’s in an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, it’s adjacent to a Site of Special Scientific Interest and it’s part of England’s only natural World Heritage Site formed by the Dorset and East Devon Coast,” explains Environment Agency project manager Megan Rimmer.

Working through the required planning, engagement and permissions took the Environment Agency and its partners, including Jacobs as consulting engineer, several years but main contractor Kier started on site in 2021.

KEY FACT

£27MCost of the Lower Otter Restoration Project

SOFT AND HARD INTERVENTIONS

The variety of work carried out on the Lorp displays a combination of hard and soft engineering.

This is most in evidence in the 70m wide breach in the embankment that is closest to the shore. This will reconnect the estuary to its floodplain and, as the embankment carries the South West Coastal footpath, a 75m long footbridge across the breach had to be built.

The bridge has a fibre-reinforced polymer superstructure with lowcarbon concrete piers and abutments.

Another of the historical embankments carried South Farm Road, a crucial local road. This was made resilient to a one-in-100-year flood event by moving it onto an embankment specifically built to support the road, raising it 4m above ground level – 2.5m higher than the old road.

“The challenges faced on Lorp are challenges faced all around our coastlines

Kier constructed the road with a 2m high temporary surcharge on top of the permanent works to speed up consolidation of the underlying ground. The embankment for the road had to have a breach in it to create a creek channel connecting the floodplains on either side. A 30m long low carbon concrete road bridge, wide enough for one traffic lane and a footpath, was built to carry South Farm Road across it.

“The main part of the bridge was built during the winter, so we had to make sure that our temporary works were high enough to be able to keep accessing them during potential flood events,” Kier project manager Darren Davis recalls.

Shrub removal across the whole of the estuary site was necessary for the creation of a more natural habitat for wading birds.

This was particularly difficult in a 4ha area that had been previously used as a landfill as wildlife like mice and worms had to be removed first. The landfill was so densely packed that these small living creatures had to be searched for by fingertip, advancing 300mm at a time.

A series of creeks with a combined length of more than 6km was created to connect up the floodplain. The primary creeks are approximately 9m wide and secondary creeks between 4.5m and 6m in width, with depths varying between 750mm and 1m. All of the materials excavated were used for landscaping across the site.

THE RESULTS

Lorp is on schedule for completion in September, but the results are already apparent as vulnerable species of birds have been spotted on site.

Environment Agency project manager Daniel Boswell believes Lorp will become a demonstrator for creating flood resilience while capitalising on natural benefits.

“The challenges faced on Lorp are challenges faced all around our coastlines,” he says. “There are lots of lessons and our hope is that it will become a showcase project of what can be done.”

These lessons will also spread overseas through Pacco.

With the newly raised footpaths across the site, Lower Otter will become an even more popular destination for visitors.

This is a winning outcome for the Environment Agency. “We’ve more than doubled the volume of the floodplain area,” says Rimmer.

“That’s 2,100 properties at risk that are defended today, [without the scheme] that would have been about 5,000 at risk in 100 years’ time.”