Future of Tunnelling | Ground freezing

Solid ground

A sustainable, safe and reliable ground stabilisation technique not widely used in the UK is experiencing significant success on the High Speed 2 and Silvertown tunnels. Gavin Pearson reports.

Ground freezing is not a new technology. It has been deployed for tunnel cross passages in many countries for a long time. But in the UK, despite a long-lived tunnelling history and extensive tunnelling in recent years, it has not been the norm.

Part of the reason for that is geology. Take London Underground. Almost all of London’s Tube tunnels are north of the River Thames. This means they run mainly through clay rather than the Lambeth Group sands found further south.

“Clay is impermeable so is easier to work with than sand. Sand has a lot of water particles and can pose much tougher challenges and instabilities,” explains Züblin project manager Jude Ronold.

Part of the reason that most of the Tube network is north of the river is because it was harder to tunnel in south London.

Indeed, such route decisions are still a factor today, with projects facing challenges like pockets of volcanic material – as seen with the Auckland Interceptor (NCE, last month). But modern tunnel boring machines (TBMs) can tunnel through almost anything reasonably safely and effectively.

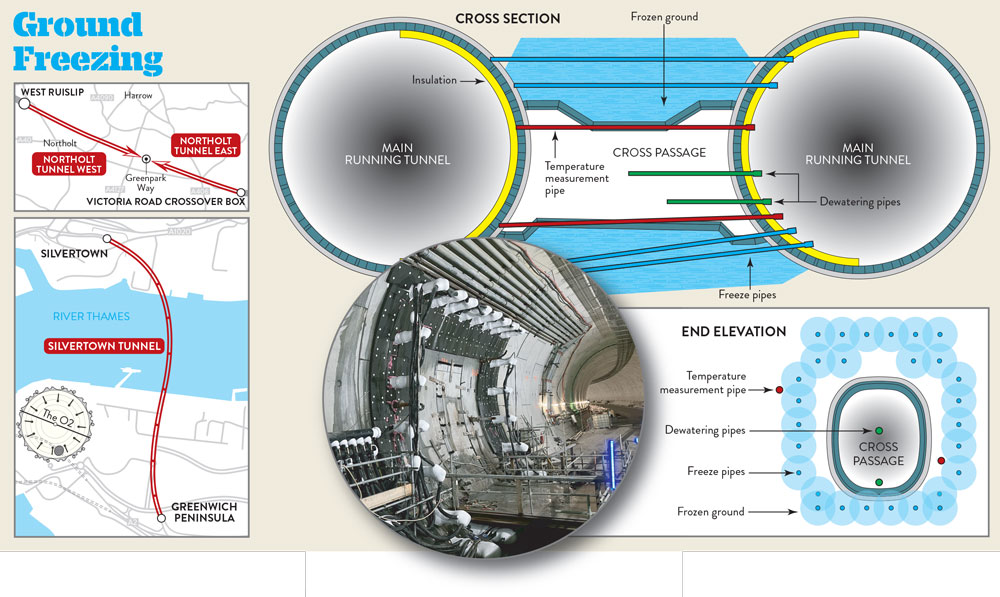

The growing need for tunnels in urban environments to avoid impacting above-ground communities, means that more projects involve tunnels built in challenging ground conditions. This has led to an uptake in ground freezing which stabilises the area around a cross passage. It comes with some advantages over other practices – as the team working on the Silvertown Tunnel under the River Thames in east London has found. There, cross passages are being built in waterlogged ground using this method.

“If you’re constantly pumping water out, you might need extraction licences. You’ve got to dispose of it once it’s out of the tunnel and there’s a lot of space taken up by the outflow, which makes work on site more difficult for all parts of the project,” explains Züblin operations manager Nick Cordon.

“There’s a point at which that becomes uneconomical and represents a risk to delivery schedules. Ground freezing is a solution to that. It means we don’t need to pump water away in such large quantities.”

As with all sub-surface solutions, ground freezing is not universally applied. It is the right solution in some situations and the team on the 8km High Speed Two (HS2) Northolt Tunnel West, in the outer west London suburbs, has been clear that everything starts from that principle.

“We did several rounds of ground investigations starting in 2017 to characterise the type of ground we were dealing with,” explains Skanska Costain Strabag (SCS JV) tunnel engineering manager for Northolt Tunnel West Phil Allvey.

Those investigations led to the discovery of a large sand channel through which cross passages – spaced at every 500m – would be dug with limited or no surface access. That ruled out the use of jet grouting and as a result, 13 of 20 cross passages are being constructed using ground freezing.

KEY FACTS

-35⁰CTemperature of brine freezing solution

13Number of HS2 Northolt Tunnel West cross passages excavated using ground freezing

IMPLEMENTATION

Having made the decision to use ground freezing, what happens next?

“We create a design layout. That can be around 34 freezing pipes and that will be based on the geological profile of each individual cross passage,” explains Ala Hammad, tunnel sub agent, Northolt Tunnels West, SCS JV. “Then, tests are taken to examine the geology – sand, chalk and so on – so we can determine thermal parameters.”

The pipes themselves are drilled into the ground around the outside of the excavation route for the full length of the cross passage. Brine freezing solution chilled to -35°C is then circulated in a closed circuit of pipes to lower the temperature of the ground gradually while temperature monitoring assesses the extent of the freeze being achieved.

What results is something akin to a long doughnut of frozen ground that surrounds the planned cross passage excavation route. This is thick enough to ensure the ground around the excavation is safe and solid. The middle remains relatively soft ground which will be excavated to form the 3.1m diameter cross passages for the Northolt Tunnel West and the 4.2m diameter passages for Silvertown.

“Ground freezing gives you the greatest stabilisation of the ground and the most effective stabilisation which you can monitor

This comes with some significant safety benefits, with recent events in India – when a tunnel collapsed in the Himalayas trapping 41 workers – acting as a reminder to the industry about just how dangerous tunnelling can still be.

“Ground freezing gives you the greatest stabilisation of the ground and the most effective stabilisation which you can monitor,” explains Allvey. “So, you have a very good idea of how the ground is going to behave before you’ve even seen it.”

The Silvertown team has also highlighted that safety plays a big part in planning for the client.

“My experience of Riverlinx [the consortium building the Silvertown Tunnel] is they put safety at the very top of all priorities,” says Cordon. “And that is probably also about trip hazards, which can be a problem on site.”

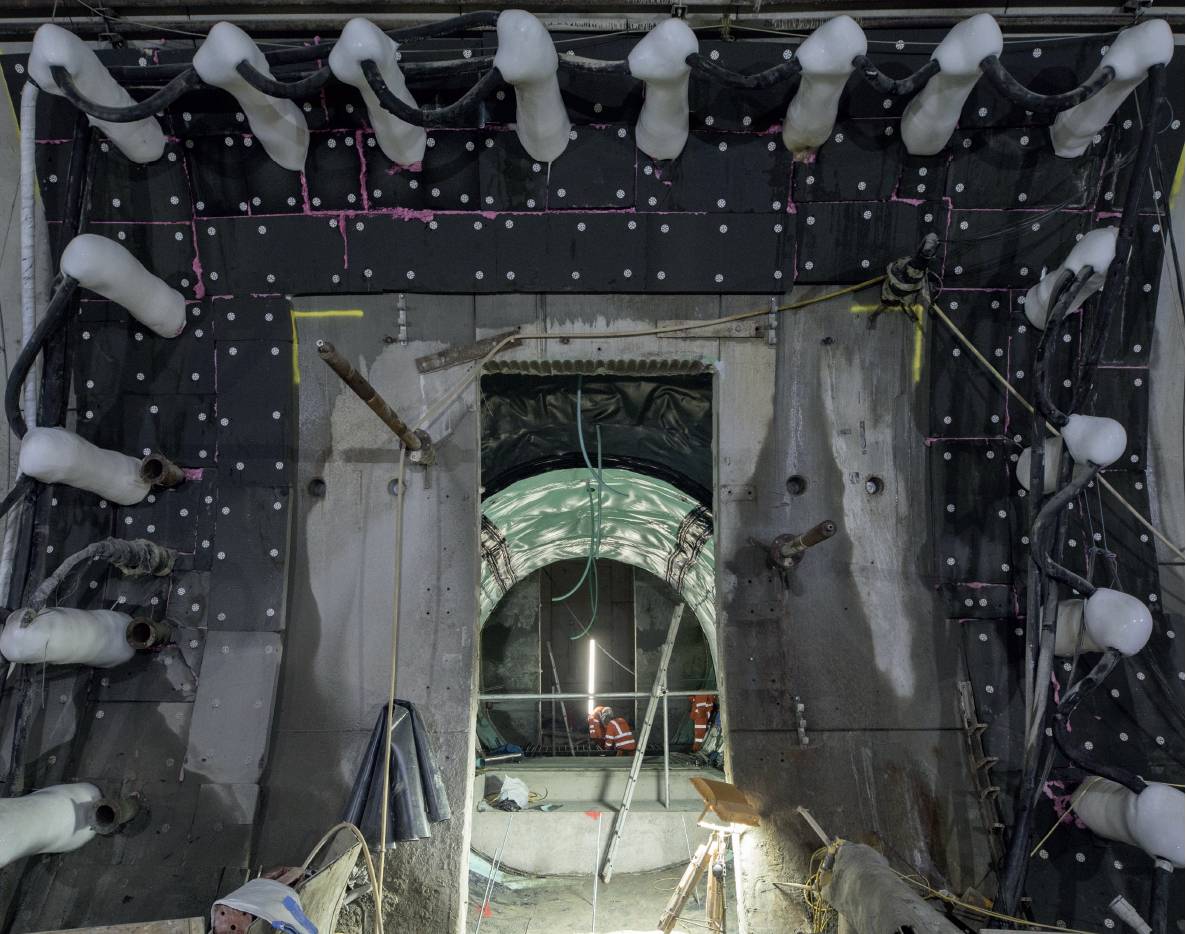

Trip hazards are something of a simplification of the logistical endeavour when digging cross passages in a busy tunnel.

The team digging the Northolt Tunnel West cross passages on HS2 had to compress its activities into a space that is small enough to allow vehicle movements along the main tunnel bore to and from the TBM. That is not easy.

Because of the space constraint, the refrigeration unit has to be reasonably compact, despite having to lower temperatures to around -35°C. Such a refrigeration unit comes in at around half the size of a shipping container. When it is set on support frames to align it with the widest part of the tunnel it takes up little valuable workspace.

Ground freezing is being used for the construction of three of the Silvertown Tunnel cross passages

Ground freezing is being used for the construction of three of the Silvertown Tunnel cross passages

This sits over a working and transport platform throughout the process, which includes drilling freeze pipes into position and excavating the final cross passages.

Part of the reason such space saving is so important is that ground freezing is not quick. That means any obstructions to other works are likely to be in place for long periods – adding to the risk of delays to the overall project.

“We started drilling on 21 June,” says Ronold about one cross passage on Silvertown Tunnel.

“Then we started freezing on 26 July. That then decommissioned on 27 November, so it’s six months for each cross passage.”

The freezing process itself can take 55 days of that time, though careful monitoring and adaptation passage by passage can help refine the solution and achieve a successful freeze a little more quickly.

“Time depends on the geology,” stresses Hammad. “And it depends on each cross passage, which has its own ‘facing design’ for the layout of freeze pipes. Our first one in the Northolt Tunnel took 43 days to freeze sufficiently to open the face.”

The length of time involved has not led to problems on either project, thanks in large part to accurate and reliable scheduling by the teams and the fact the method creates a highly reliable and certain excavation environment.

In both cases, the ground freezing process was scheduled for after the TBMs had passed and a lot of co-ordination and planning went in early to ensure that any possible problem could be prevented. Indeed, the success of the approach has seen additional cross passages agreed for the same practice on the projects.

WIDER UK ADOPTION

So, will ground freezing become more widespread in the UK?

One reason to think it will is the environmental impact – or relative lack of one. Along with a major reduction in water extraction, ground freezing can be done without waste coolant remaining behind in the ground, unlike methods that use grout as a stabilising material.

This is because the freezing solution can be pumped through the ground using pipes in a closed loop. As a result, relatively little of it is needed and there is no lasting impact on the surrounding geology.

And the solution itself is remarkably low risk. “It’s calcium chloride – salt, really. We use brine,” explains Ronold.

“And brine can be reused so once it is removed from the same pipes it went in through, it can be put into stores and reused for other projects.”

So wider adoption is now about whether it works well for clients. “I think it’s been a success,” stresses Cordon about Silvertown Tunnel.

“Brine can be reused so once it is removed from the same pipes it went in through, it can be put into stores and reused for other projects“Ultimately it all worked out through a lot of the effort that went in before implementation. That detailed preparation meant there was a lot that didn’t go wrong on site.”

The Northolt Tunnel team agrees.

“A client that now knows this has worked on a similar project can be crucial to decisions about using ground freezing on new projects,” says Hammad.

Of course, one thing that may hold that back will be skills. The UK still has limited experience in ground freezing and support from abroad has played a big part in the Silvertown Tunnel and on HS2. It is no accident that Züblin, which was awarded the ground freezing contract by Riverlinks, has 78,000 people behind it all over the world.

“In the UK the strategy is based on having multi-skilled teams,” explains Gustav Jahnert, business development manager at Züblin Ground Engineering UK. “We have to make sure we have a number of core teams here for ground freezing but who could also be deployed on something like a piling project or a grouting project.

“We focus on delivering with local teams and at the same time we bring in expert knowledge from within the wider group – such as our ground freezing department based in Berlin, which is continuously delivering ground freezing around Europe.”

This approach, and good knowledge sharing across the Silvertown and Northolt tunnel projects bodes well for ground freezing in the UK.