Net Zero | CCUS

Clusters of opportunities

As the UK’s carbon capture, usage and storage (CCUS) plans move from intention to reality, we look at what it means for the construction sector. By Kristina Smith.

On 10 December, two major UK carbon capture projects reached financial close, with construction scheduled to start this year: Northern Endurance Partnership’s pipelines and infrastructure to transport carbon dioxide offshore for storage and Net Zero Teesside (NZT) Power’s new gas-fired power station with carbon capture.

Both projects are part of the East Coast Cluster, which will eventually see carbon dioxide captured from multiple industrial facilities – as well as from the new gas-fuelled power station – and then collected, compressed and transported down pipelines onshore and offshore to be stored under the North Sea.

For WSP technical director Dominic Cook, who leads a team providing advice to the UK government on carbon capture, usage and storage (CCUS), this was a big day. “The fact that we have had the first financial close is a big step forward. This shows that people have taken on the risk. That creates confidence,” he says. “And, from a personal perspective, it’s a massive relief that it’s over the line, having started working on this 16 years ago.”

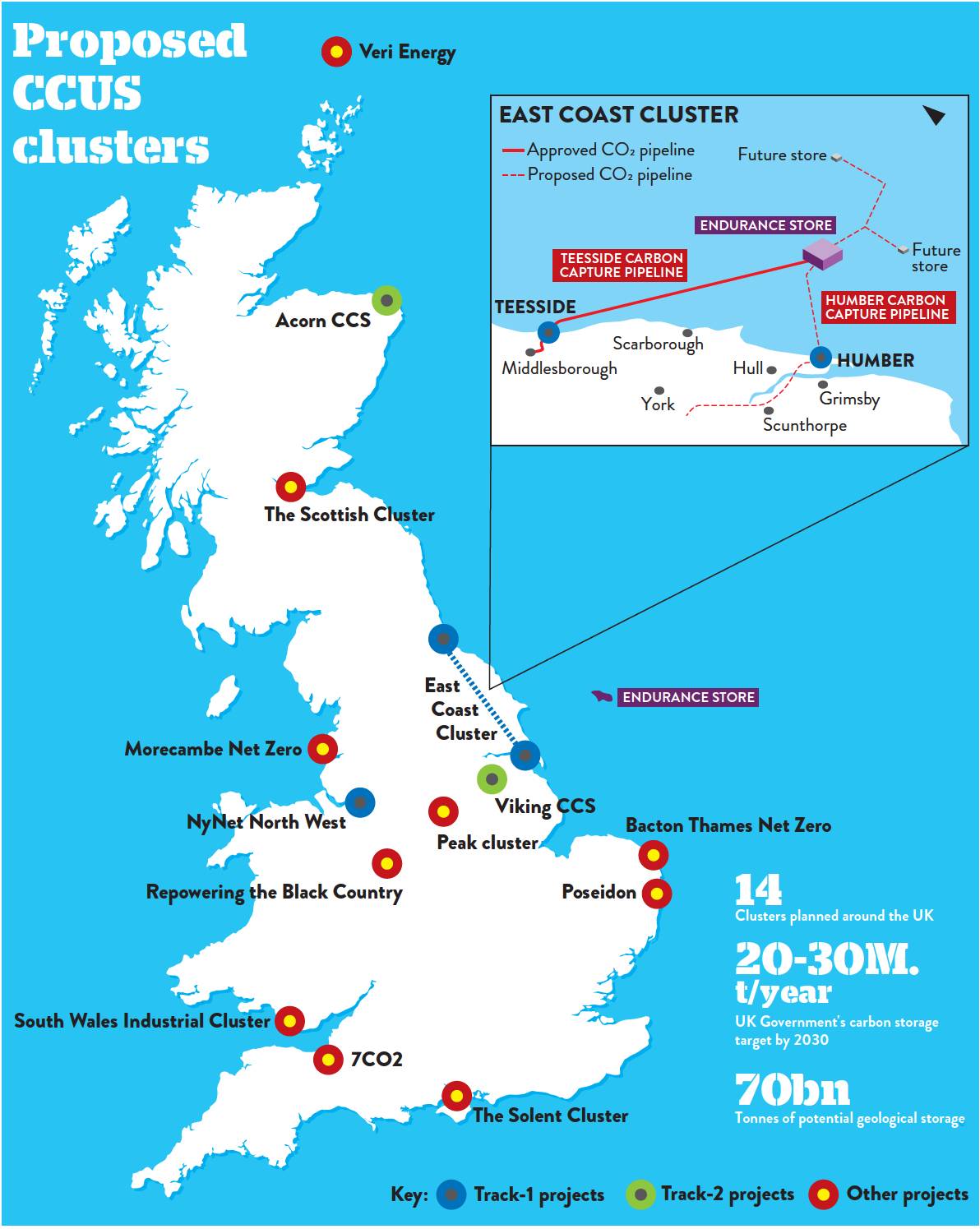

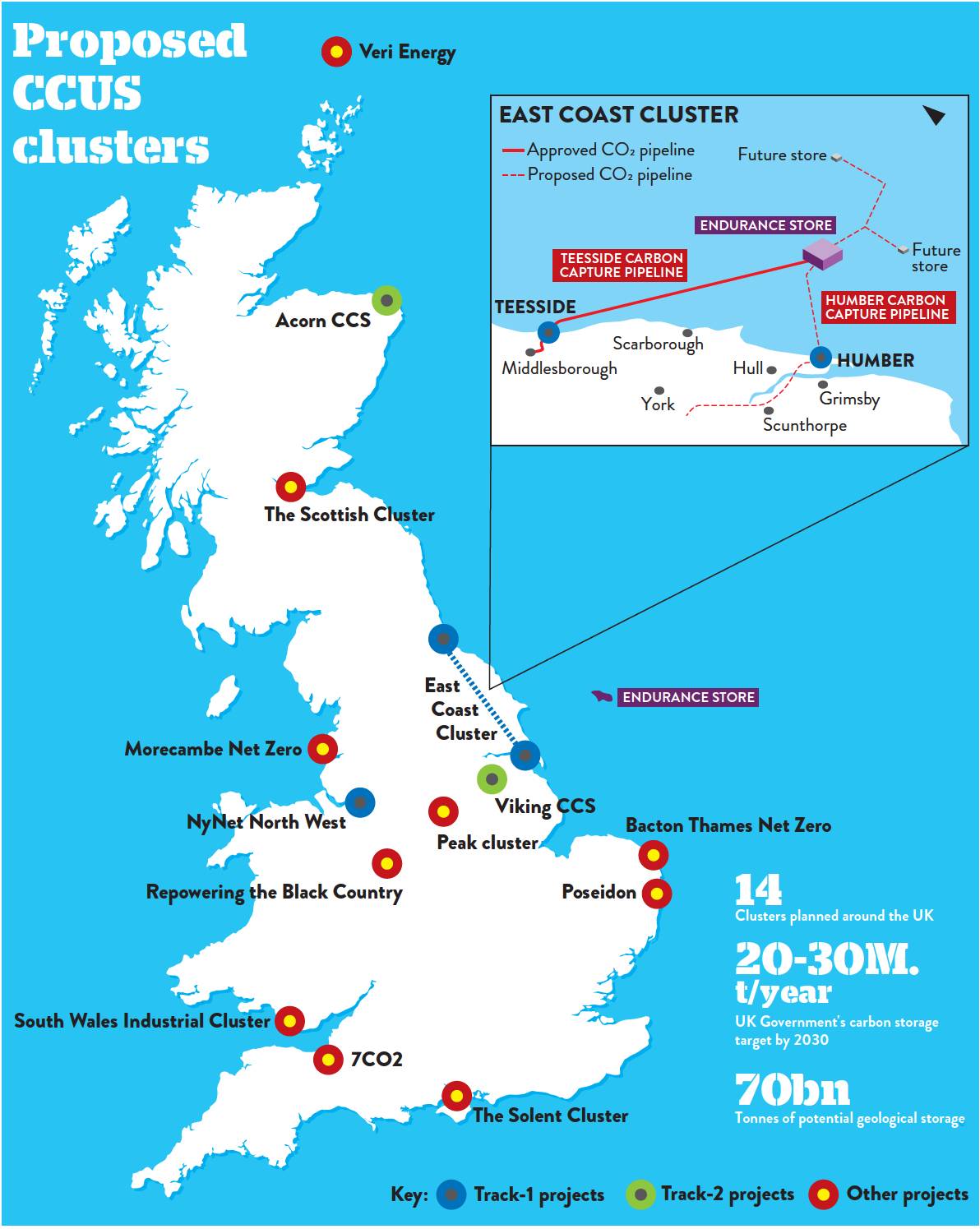

The East Coast Cluster – which will see carbon emissions from facilities in both Teesside and the Humber piped 145km offshore into the Endurance saline aquifer, 1000m below the seabed – is one of 14 clusters planned in industrial areas around the UK. Creating these clusters will add up to tens of billions of pounds worth of work.

According to Olivia Powis, CEO of the Carbon Capture and Storage Association (CCSA), the private sector is already providing upfront investment, which could reach between £20bn and £30bn by 2030 to meet the government’s carbon storage targets of 20-30M.t a year by 2030 and 50-60M.t a year by 2035.

As an indication of what proportion of that spend could come to the civils sector, Spirit Energy has said that of the £5bn it will be investing in infrastructure for its Peak Cluster CCUS, around £1bn of that will be spent on civil engineering works.

FALSE STARTS

The concept of CCUS is relatively straightforward: carbon dioxide is extracted from the flue gas of a power or industrial plant, transported by pipelines, some of it is used and the remainder stored underground. Technologies for using the carbon dioxide – such as sequestering it into aggregates or breaking it down into synthetic fuels – are not yet viable in the UK, which is why we currently tend to talk about carbon capture and storage (CCS) rather than CCUS.

CCS was first deployed back in the 1970s in the US – although not for environmental reasons. This application sees carbon dioxide captured from natural gas and then injected back into underground reservoirs to make the extraction of oil easier. Norway’s Sleipner and Snøhvit CCS schemes also store carbon dioxide captured from natural gas and have been operating since 1996 and 2008 respectively.

Boundary Dam in Canada is seen as a milestone project because it was the first power station to use CCS on a commercial scale. From 2015, it has been deploying CCS with one of its generator units.

“How we allocate risk could have a significant impact on the cost

Looking at contemporary CCS projects, some countries have edged ahead of the UK, says Cook. Norway’s Northern Lights CCS which will store carbon dioxide from various industrial sources, started operating in September. Development of the Netherlands’ Portos and Aramis projects is also underway.

The UK, which boasts over 70bn.t of potential geological storage according to the British Geological Society, has had a few false starts with its CCS programme. In 2005, a project at Peterhead gas power plant was proposed but could not secure funding. The government then twice launched competitions to deliver and operate CCUS plants – in 2007 and 2012 – and twice abandoned them.

In 2020, the government came up with the cluster approach, which aims to site storage close to existing groups of industrial plants. In 2021, it announced that the East Coast Cluster and the HyNet Cluster in northwest England and North Wales would go ahead, known as Track-1. In 2023, it said that the Track-2 clusters of Acorn in Scotland and Viking in Teesside would be developed.

One of the biggest barriers to building CCS facilities is their cost, for both construction and operation. Extracting carbon dioxide from flue gases takes huge amounts of energy. “The general rule is the more carbon dioxide you want to capture, the higher the energy penalty becomes,” says Tom Ilett, associate engineer, energy transition at Aecom.

It currently costs between £100 and

£200 to store a tonne of carbon in the UK

It currently costs between £100 and

£200 to store a tonne of carbon in the UK

Currently, the cost of storing a tonne of carbon dioxide is between £100 and £200, says Ilett. That compares to a cost of carbon per tonne under the UK Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) of £41.84 as of January 2025.

Although the cost of carbon is projected to rise, there will still be a discrepancy when these facilities come online. That’s why in October 2024, the Government announced funding of up to £21.7bn over 25 years, which will go to the first two CCS clusters to make up the difference between what it would cost to pay for emissions and to store carbon.

The CCSA has been looking at ways to reduce the cost of CCS projects and will be producing a report on the subject soon. “How we allocate risk could have a significant impact on the cost,” says Powis.

A key challenge, she explains, is managing and coordinating the timelines for the many moving parts of a CCUS value chain. More collaborative contractual structures, with a systems approach to problem-solving, could help reduce that risk. Technology costs will also come down as more projects get underway around the world, she adds.

Construction costs could drop with more projects, says Cook: “Within the contractor supply chain, there may be conservatism for the first projects, given it’s a relatively new business model. The more you do it, the more cost-efficient you get around delivery.”

WHO WILL BUILD THEM?

The infrastructure needed for a CCS cluster is extensive, spanning onshore and offshore installations. Although some parts of these mega projects will be delivered by companies from the oil and gas sector, there will be a huge demand on the construction sector too.

Balfour Beatty is part of the consortium building the new NZT power station in the East Coast Cluster and Costain has the contract for the onshore pipeline.

“The number of people needed to build this infrastructure will be unreal,” says Ilett. “These are enormous multiple infrastructure projects, big power plants, pipelines and offshore installations and retrofitting industrial plants on a scale we have not seen in my lifetime.”

At industrial or power plants, civil engineering companies will be called upon to design and construct the tall cooling and absorbing towers and associated infrastructure. These are significant developments. “With a power plant, you are doubling the footprint,” says Ilett. “In some places, if you are trying to retrofit, you cannot do it because of the space requirements.”

Carbon emissions from Teesside will be piped 145km offshore into the Endurance saline aquifer, 1000m below the seabed Credit: Wood/Net Zero Teesside Power

Carbon emissions from Teesside will be piped 145km offshore into the Endurance saline aquifer, 1000m below the seabed Credit: Wood/Net Zero Teesside Power

Although building a new gas-fired power plant within the East Coast Cluster has attracted criticism, it is necessary while the UK renewable energy capacity ramps up, says Ilett: “We need alternative power generation to fill the gaps when the renewables cannot provide enough power to the grid.

“Even with a huge penetration of renewables and large amounts of battery storage and pumped hydro, we will not have enough energy, certainly for the next 20 or 30 years, which is the life of these carbon capture projects.”

The pipelines themselves are similar to natural gas pipelines and are likely to be delivered by companies who already work in that sector. In a few cases – such as for the HyNet pipeline in Liverpool Bay – it may be possible to re-use sections of existing natural gas pipelines.

Onshore, pipes will be mostly laid in open trenches with techniques such as horizontal directional drilling, used where they run under existing infrastructure such as roads or rail.

The offshore works for CCS infrastructure will include pipelines, subsea injection systems, power and communications cables and offshore systems engineering.

PROJECTS IN WAITING

The CCSA has identified a total of 90 projects that are looking to deploy CCUS. Some of these are linked to the 14 clusters, some could be linked into them and others further afield might consider means other than pipelines for transporting carbon dioxide to storage. Together, these could add up to over 90M.t of carbon dioxide being stored every year.

Among these projects in waiting are those linked to the Peak Cluster in the Peak District, where 40% of the UK’s cement is produced, due to the area’s geology. The cluster is made up of five of the area’s cement and lime plants located in Derbyshire, Staffordshire and Cheshire – owned by Tarmac, Breedon, Lhoist, Aggregate Industries and SigmaRoc – with UK clean energy project development company Progressive Energy.

CCS is a vital piece of the decarbonisation journey for cement and concrete, since around half of the carbon emissions associated with cement come from the chemical reaction itself. The Mineral Product Association’s map to net zero shows around 60% of carbon emissions being captured and stored to meet the 2050 target.

“We are urging the Government to move forward on allocation for projects so that the clusters and projects can bid into them and investors and projects can understand the scale of future opportunities

The plan is that Peak Cluster will capture and store 4M.t of carbon each year in the Morecombe Net Zero storage facility, owned by Spirit Energy. The Cluster has also said that it could be possible to connect to the HyNet facility in Liverpool Bay.

“In cement plants, the carbon dioxide concentrations are relatively high which allows a higher, more efficient capture rate of over 10%. It’s much easier, which is why the cement industry lends itself to carbon capture,” explains Matt Browell-Hook, energy transition director at Spirit Energy. Spirit Energy plans to provide storage capacity and associated infrastructure for the Peak Cluster group and other emitters and he adds that since cement plants run consistently, the systems engineering is easier than for gas fire-powered plants designed to be run intermittently to top up the grid.

Each producer will build their own carbon capture units next to their existing plants. Captured carbon from each one will be compressed and transported through 180km of onshore pipeline and 75km of offshore pipeline to be stored in empty oil and gas reservoirs beneath the eastern Irish Sea, 25km Southeast of Barrow-in-Furness.

Spirit Energy – which is owned by Centrica and German energy and infrastructure firm Stadtwerke München – has been extracting oil and gas from this area for the past 40 years, with reserves due to run out at the end of this decade.

“We know the reservoirs are ideal carbon stores for the future,” says Browell-Hook. “They have a layer of salt and mudstone on top of them that makes the reservoirs impermeable so that the gas won’t move into higher layers of rock.”

Spirit Energy received a carbon storage license from the North Sea Transition Authority (NSTA) – which regulates the UK’s offshore carbon dioxide transport and storage industry – in May 2023 and carried out a seismic survey over an area of 500km2 2 last year. This year, it plans to launch the Development Consent Order for planning for the pipeline and other construction elements. If sufficient certainty can be achieved, construction contracts will be let in 2028, ready for carbon to be stored in 2031.

UNCERTAINTY SCARES INVESTORS

While investors in the Track-1 clusters of East Coast and HyNet can have confidence that their projects will go ahead, the same cannot be said for the other 12 projects. Even the two Track-2 clusters that have been selected are waiting to hear from government about which of their possible anchor projects will be given the green light before they can progress.

The others face uncertainty: “Our biggest challenges are policy and regulation,” says Browell-Hook. “We are outside the Track-1 and Track-2 process, so we have no route to market. We are looking for certainty of future regulation, what funding will be available and how we access that in order to meet the carbon budget and bring the lowest level of cost in the future.”

The lack of clarity – especially coming after the UK’s two false starts with CCUS – increases risk for investors. In October 2024, ExxonMobil pulled out of its involvement in the Solent cluster, saying in a statement that it had been trying for three years to get certainty from the UK government that would allow it to commit to the investment needed.

“We are urging government to move forward on allocation for projects so that the clusters and projects can bid into them and investors and projects can understand the scale of future opportunities,” says Powis. The longer projects and investors must wait for decisions, the greater the risk, and hence the greater the cost which bidders must allocate for that.